Trump, National Power, Freedom Abroad

Podcast with guest Elliott Abrams. Also: What the USA can learn from the KGB about dealing with Iran’s assassins

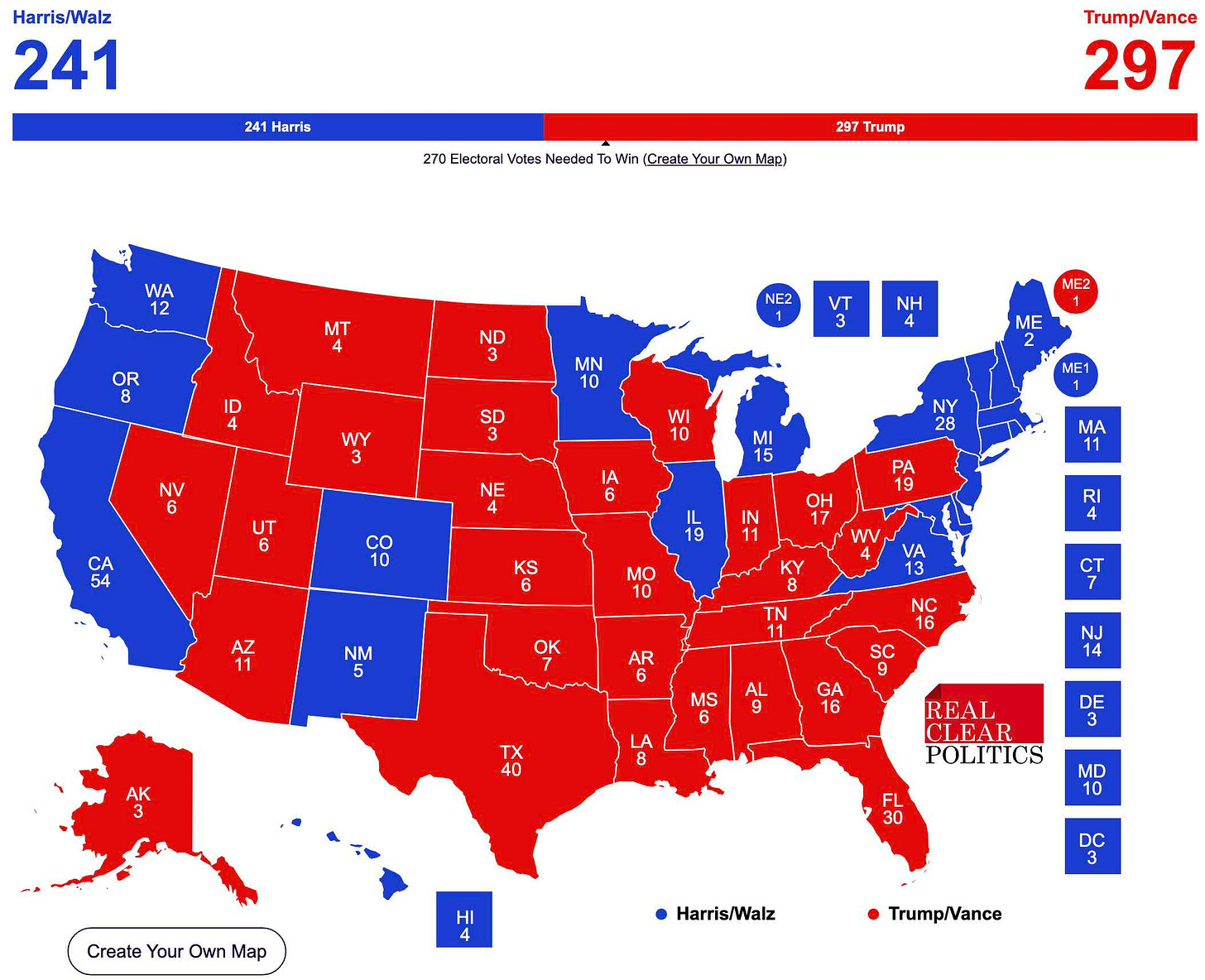

What will happen to American power and freedom in the world in a second Trump administration? The question is more than just academic as former President Donald Trump closes strongly in the final week of campaigning and voting.

Privately, some Democrats are despairing that Kamala Harris and her running mate, “Tampon Tim” Walz, will lose them the White House and hand both houses of Congress to Republicans. Time is up for silly Kamala, despite being “brat,” and her campaign of joy and being unburdened by what has been, or whatever.

But as one looks around the world, there is much to cause worry: tyranny, an aggressive China, Iran starting wars, unfair trade, the metric system.

Furthermore, by the progressives’ telling, Trump is part of a worrisome wave of authoritarianism that goes hand-in-hand with meanies like Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese Communist Party boss Xi Jinping. Only more tampons in boys’ bathrooms, pronouns on email signatures, the Biden-Harris Europe-first foreign policy, and homages to the make-believe “rules-based international order” can save the day. To disagree is to be a fascist.

In reality, only a Trump victory can restore the free world’s prosperity and confidence in itself. That traditional role for America, forecast by John Winthrop in his 1630 sermon in the Massachusetts Bay colony as “being a city on a hill” that inspires people elsewhere, will be revived when we have a president who ignites the economy and doesn’t apologize for America. That prosperity and confidence combined with a radically transformed military will restore Fortress America.

This approach fits well with our heritage. As Calvin Coolidge said, “the chief business of the American people is business.” His predecessor, Warren Harding, won a landslide with 60 percent of the vote in 1920, promising (and delivering) a “return to normalcy” after war and plague and accompanying big government had upended American life.

But, beyond serving as a role model, what is the best use of American power in a Trump II administration? Is it not still necessary to attempt to shape the world more directly—at least by backfooting our opponents? One way to shape foreign policy outcomes is to emphasize human rights, but human rights efforts have gotten a bad reputation in recent years—largely because the progressives have screwed them up.

Ronald Reagan used human rights to personify the evil nature of those regimes most likely to threaten the free world’s security, and to demonstrate confidence in our superior free societies. We also criticized our allies when appropriate—and we had a lot of authoritarian allies during the Cold War—but we were not under the illusion that the human rights situation would improve if those allied governments were replaced by ones that were communist or Islamist.

Progressives and the national security blob have abandoned Reagan’s approach and gone back to something like the warped human rights efforts of Jimmy Carter, which ended up aiding communists and Islamists in places like Nicaragua and Iran. President Joe Biden has criticized important partners like Saudi Arabia while essentially giving passes to far more abusive adversaries like China and Iran. The cause of human rights has also been conflated with the Ukraine fiasco. It is understandable that some skeptics would quietly dispense with the whole human rights project, given its failures abroad and use as a political tool against non-progressives here in America and in conservative-led democracies like Hungary. What do we get for supporting exotic liabilities like Taiwan or muddying crucial discussions with Putin, Xi, and North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un with morality?

A question today is how a would-be Trump II administration will handle human rights. Critics say Trump is chummy with dictators and strongmen and doesn’t really care about the issue. I say his first term paints a picture with a lot more nuance. In fact, Trump just told Hugh Hewitt that he would press China to release Jimmy Lai, the publishing tycoon that communist authorities in Hong Kong have locked up for having a surfeit of opinions.

In the latest edition of Domino Theory, Mark Simon and I discussed the matter with Elliott Abrams. Elliott recently received high praise from the pinkos at The Nation, who labeled him a "Convicted Liar, Defender of Dictators, and Accomplice to Genocide.” Clearly he must be saying or doing something right.

Elliott on current and past policy toward Iran’s Islamist regime:

My complaint about our Iran policy, goes well beyond the area of human rights.

We've been letting Iran get away with murder for decades. I mean, murder of Americans for decades. There's only two times, I think, Reagan in ‘88 sank about half their Navy, and then Trump killed Soleimani, the head of the Quds Force of the Revolutionary Guards. In between those, and since those, they're still trying to kill Americans.

And they are basically immune. So they keep doing it. On the human rights side, we've always been in favor of democracy and human rights in Iran. The people of Iran are the ultimate answer to that regime. They hate the regime. If they could get rid of it, they would.

And every three or five years, they rise up again, and are crushed by this regime. Sooner or later, that regime will fall, whether it's a year from now or 30 years from now, we don't know. And we've never been able to predict that kind of thing. What we have not done is concentrate as much as we should on human rights in Iran.

Elliott on dealing with the Chinese, what has worked on what has not:

There's been a wonderful change with respect to American views of China if you compare to twenty years ago. Americans get it now that China is a predatory regime people get it about the regime and the Chinese Communist Party people understand what an evil force they are and what a dangerous force they are. Partly you have to credit President Trump with explaining how China has hollowed out parts of our economy so that's a very good thing to understand.

What can we do for human rights? If we have a good relationship, I'm not talking about a friendly relationship but a working relationship on a number of issues. If a president can talk to Xi Jinping, I think the thing to do is keep mentioning this, keep working at it.

I worked for [then-Secretary of State] George Shultz in the Reagan administration and he had a very good idea, which was always put human rights at the top of the agenda. If it's at the bottom of the agenda, they're going to notice that. Also, meetings go long, people get tired. People are going to say, “Oh, six o'clock, time for dinner.”

In the Bush administration, we got a number of people out of jail in China. We did it quietly. Clark Rant, Sandy Rant, who was the ambassador, always said, “I can make a big splash, attacking them, but I think I might be able to get so-and-so out if we do it quietly.” And he actually did get a lot of people out I think what President Trump should do is raise this and say to Xi Jinping, “You know, there are real limits on what I can do in a democracy If you keep doing X and Y and Z. Give me something make this relationship work.” Now, he's not going to turn Hong Kong into the flower of democracy, but in the case of China dealing with somebody like Xi Jinping, I am talking about case work. I am talking about named individuals. The Biden administration has tried it, but they project so much weakness that I think if you're in the Chinese government, you don't feel much pressure about that.

In the case of Russia, what Biden did was, trades. And people are always interested in trades.

So you can do that if that's possible with China. But I think it's important that they understand this means something to us ideologically and politically. The administration is going to get creamed if it looks as if they're indifferent.

Elliott on human rights and non-democratic allies, especially in the wake of the disappointing Arab Spring:

On the question of [former Egyptian President Hosni] Mubarak, Morsi, the army in Egypt, and on the question of Saudi Arabia.

I want to throw in a word that I think is important here, legitimacy. I would argue that the government of Saudi Arabia is legitimate, in the eyes of its own people. Legitimacy basically means that they don't think there's a realistic alternative that would be better for them.

I think, Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince, has been very smart in sort of thinking about, what people want? It's not democracy in his case at all…

Mubarak toward the end was losing his legitimacy. Partly for the same reason that Assad did in Syria and Qaddafi did in Libya, which was he was turning [his government] into a monarchy. There was a kind of royal family and the thought was, which son of Mubarak is going to take over?

It was actually going to be Gamal, his older son. Which son of Qaddafi, he had several, is going to take over? And the Assad family, same thing. People don't want that. People in those countries judged they had increasingly illegitimate government. [Muslim Brotherhood stand-in] Morsi, won an election and then proceeded to attempt to make sure that was the last election they ever have. So when the Egyptian army overthrew him, I would argue they did it with public support. Egyptians had figured out that these Muslim Brotherhood guys were not talking about democracy. They were talking about running the country in accordance with their ideology.

Later, he added:

The danger you always have is, you want to use human rights as a weapon against your enemies. But you drop it when it comes to countries that are more or less on your side.

Reagan figured out that if you do that, then you don't have a human rights policy at all. It's just another weapon against your enemies. You need a realistic human rights policy. You can't ask people to commit suicide. They're not going to do it, but you can make an argument for improvements that are sensible, that are incremental. In the Emirates and Saudi Arabia, it's not going to be elections, not going to be a parliament. Maybe it's religious freedom. Maybe it's a little more freedom of speech. Maybe it's a little more freedom of the press. And obviously the trick is to figure out, “What will the traffic bear in this country?” And again, I think we did some of that in Trump administration. We didn't do enough in the case of Iran. I think this goes back to 1979. No administration has really done enough.

Mark on keeping Chinese Communist Party princelings and other kids of bad guys out of U.S. colleges:

Believe me, there's more than enough to fill our schools. We don't need them. I often said that if you really wanted to start a riot in China is, and are, you probably start a riot, some of the U.S. admissions offices, is if you just said, you're a member of the Chinese Communist Party, here's the list, here's your name, you're not coming: There would be 20,000 people protesting in front of the U. S. embassy tomorrow. But at the end of the day, that protest would turn on the Chinese because all we'll say is it's not our problem. It's yours. And I think it sends a powerful message because really the message is, and I see this so much in Hong Kong and in China when we accept these people, we undercut ourselves so much.

Christian and Mark finish off that part of the dialogue with some Soviet history in dealing with Iran’s terrorist proxies:

Christian Whiton: One, it's funny, we have what you say about Iran [killing Americans and threatening to assassinate former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo]. We have a case study of what works and what doesn't, and I think you were a part of or the heart of this or at least adjacent to this in the Reagan administration and Mark does a better telling the story than I do, but I'm going to tell it anyway, which is that Hezbollah's predecessor in Lebanon was taking foreign officials hostage, including American officials, some of whom they killed, others they held hostage for a long time. They tried that trick on the KGB and instead of sending an angry letter, the Soviets grabbed one of the kids of the predecessor of Hezbollah and chopped off a finger or ear…

Mark Simon: They sent the ear back and said, more body parts coming. They picked up more than one kid. They were, you know, they did their thing. They got their guy back.

Christian Whiton: So that's what works. We know that doesn't work. Not that I'm necessarily in favor…

Full Transcript of the Episode (see below for video and audio links)

Parting Shot

Back in olden times when The Simpsons was still good, the writers had Sideshow Bob run for mayor of Springfield. They didn’t capture the essence of Republicanism, but they produced the best parody of it. Bob’s summation:

Your guilty conscience may move you to vote Democratic, but deep down you long for a cold-hearted Republican to lower taxes, brutalize criminals, and rule you like a king.

Good luck next Tuesday. May the best man win.

Listen to or watch the podcast episode featuring Elliott Abrams on Spotify

Listen to the episode on Apple Podcasts

Watch on our YouTube Channel