By almost any historical standard, U.S. equity markets are radically overvalued and ripe for a correction or a period of prolonged stagnation. For those of us who doubt the ability of experts, much less amateurs with day jobs, to pick investments that will beat the market over the long term, our preference is often to buy and hold equity, or better yet ETFs, and ride out downturns. But the market might be nearing Dutch Tulip Mania levels—and it may be time to head to the sideline.

(Image: Wagon of Fools by Hendrik Gerritsz Pot, 1637)

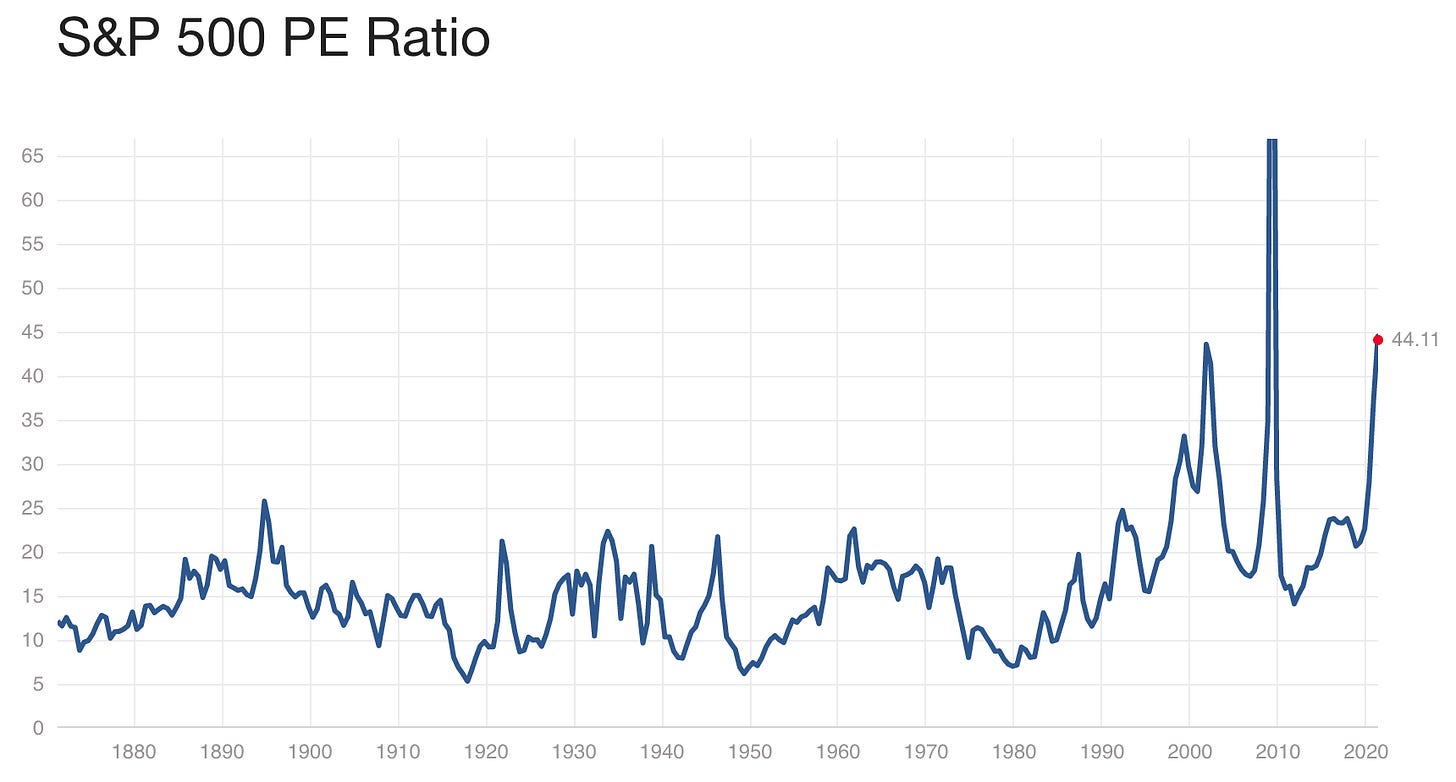

For starters, look at the price to earnings ratio of S&P 500 index companies. Price stands at a whopping 44 times annual earnings, whereas the average over the last century is closer to 16 (or a little higher if you date the modern economy from the 1980s or 2000s). If a restaurant made just $100,000 in profit last year, would you pay $4.4 million for the business?

But price to earnings can be misleading in times of economic distress. As the chart above indicates, P/E was at its highest during the 2008-2009 recession when the markets tanked. That was because few companies were making much earnings—the denominator of the P/E fraction. You can see similar spikes in the early 2000s recession and today. Furthermore, when red ink is flowing in the streets, companies take advantage of the turmoil to write down overvalued assets since the consequences for doing so are lessened and can be blamed on the economy, which exacerbates the trend of low earnings. So it is useful to look at the ratio of price to a company’s top line revenue in addition to price to earnings in times of turmoil, since revenue is far less likely to evaporate and is harder to manipulate.

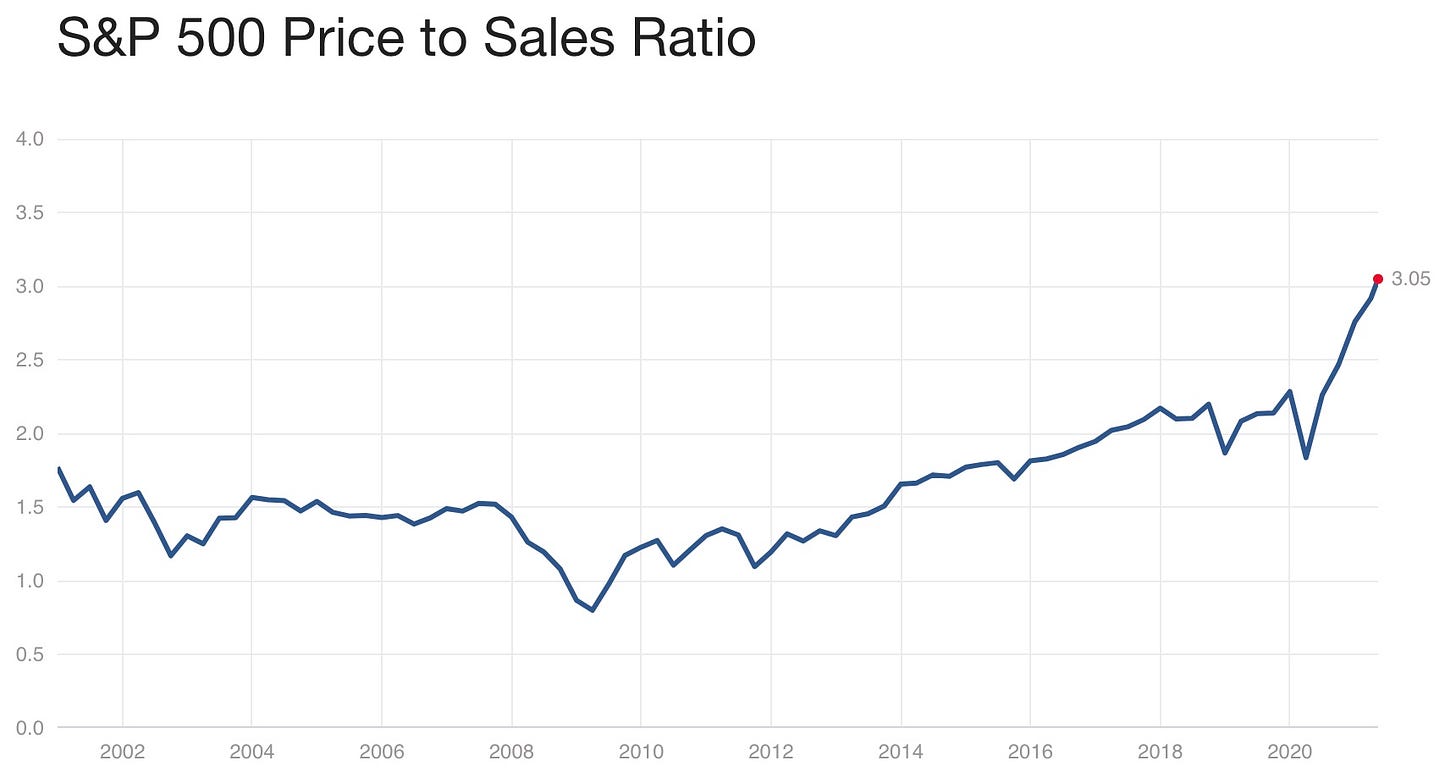

Unfortunately, that chart is even more horrifying. Price to sales should be about 0.8 to 1 for steady companies with thin but solid profit margins, and perhaps 2 or more for fast-growing, profitable enterprises. Across the S&P 500, the historic average is 1.6. Today, it stands at an all-time high of 3, eclipsing previous bubbles. Even during the dotcom bubble that popped in early 2000 that ratio only reached about 2.4.

Other signs of a bubble in equity markets abound. Companies with no profits are going public. SPACs allow for IPO-like equity placements while circumventing scrutiny from analysts and regulators. Cryptocurrencies are a topic for another day, but the current leading cryptos are priced solely on the basis that there is hopefully a greater fool willing to pay the same or more—not on any intrinsic current or future value. The mentality that one must grab a piece of the Wild West of crypto while the getting is still good is similar to that held by investors prospecting zero-income internet stocks during the late-90s bubble.

Beyond high prices relative to historic benchmarks, the true hallmark of a bubble is that investors convince themselves it is different this time. Abetted by the corrupt financial media and its puffery, some investors are concluding just that. In the late 90s, the internet was going to change everything and bring untold efficiencies, justifying sky-high stock prices. It did eventually change just about everything—except that investors still didn’t want to overpay for future earnings, and markets eventually corrected.

Arguments this time around are that interest rates will be low forever, increasing the present value of future earnings from companies. The pandemic has taught us how to use technology better leading to untold increases in productivity. The demand for hardware and software and broader tech is insatiable. And growth is exploding since the economy will be fully reopened this summer.

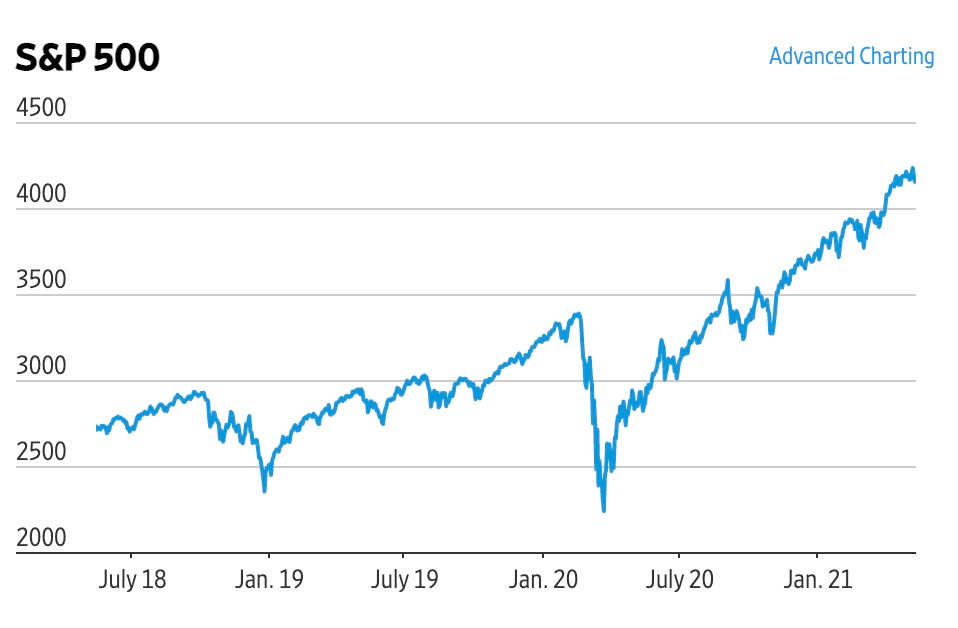

The reality is that inflation is real and almost certain to escalate given the Fed’s reckless printing of dollars beyond any historical precedent. Part of American business that doesn’t need to be in the office every day will benefit from a new hybrid of splitting time working from him and going to the office. However, the productivity gain from that will be nothing compared to the mass availability of the PC or commercialization of the internet. In other words, it will have less impact than past breakthroughs that didn’t fundamentally change investing. Most important, the run-up in the market since the pandemic bottom has already priced in a full reopening of the economy and recovery of lost GDP and earnings. The chart below shows the climb back, which began in late March 2020.

Last but not least is the dumb money. Americans have a well-earned and growing skepticism of the expert class, but that does not always mean amateurs have superior knowledge. In the old days, before internet trading, real-time quotes, and shares that cost $2000 a piece, brokers preferred that their customers buy only “round lots” of 100 shares or a multiple thereof. “Odd lots” of fewer than 100 shares would usually trigger a higher fee and were associated with investors with little money and who were more susceptible to fads. Some newspapers, to which one turned for the previous day’s closing prices, would occasionally print the equities with the highest number of odd lot trades. The theory was that this was the least informed money in the market and the investments were best avoided.

Today, a good portion of the hype around the market is coming from the modern-equivalent of odd lot traders. The saga of investors on Robinhood’s platform and their success of burning pedigreed poohbahs who were shorting GameStop and other vulnerable equities is heartening. Americans love it when underdogs beat the snobby, elite professionals. Furthermore, opaque Wall Street practices like allocating IPO shares could use some democratization. But, as with crypto, the surge of investment around these companies and platforms feels a lot like gambling. It is divorced from the idea that a company is worth something because it will produce future earnings or be acquired for more than its current value. It sounds a lot like cashiers and waiters talking up their Netscape stock in 1999.

Last but not least, there are the other troublemakers in Washington apart from the Fed. A White House proposal effectively to double the capital gains tax on high earners would alone cause a massive selloff to realize gains at this year’s lower rates if investors ever decide the proposal is real. Washington is also determined to raise energy prices for everyone and shift capital from the productive private sector to the unproductive public sector.

It might be time to reprise the old adage, “Sell in May and go away.” The quip apparently emerged in Britain when well-healed traders would depart London for the summer. (Even during spring and fall, bankers there observed an elegant 3-6-3 rule: take in money and pay depositors 3 percent, lend it out at 6 percent, and be on the golf course by 3 pm.)

The phrase made its way to New York, whose stifling summers were typically marked by low trading volume, traders on vacation, and the possibility of market-moving events that could take investors by surprise given the inattention of summer.

Alas, as with most efforts to time the market, this one is a losing strategy over the long run. But this year, with sky-high valuations, a full recovery already priced into stocks, speculation by investors who possess the least information, and an out-of-control Washington, the strategy might make sense.