Hegseth Should go to Hill With Team and Vision

Trump’s unconventional nominee to lead Defense Department should spark debate about the military America needs.

President-elect Donald Trump is not afraid to give a tough job to his yet-to-be named legislative team. It will be up to them to get his Cabinet nominees confirmed by the Senate, along with a handful of other senior positions before the team hands nominations off to relevant departments and White House legislative affairs when the transition goes kaput after Trump’s inauguration.

I was involved in this process during Trump’s first transition. With a narrow majority of 52 Republicans in the 115th Congress, we had little room for error. We picked up four Democrats for Secretary of State-nominee Rex Tillerson, leading to a 56-43 vote. The transition’s closest vote was Betsy DeVos for Secretary of Education. She passed 51-50 with the Vice President breaking a Senate tie for the first time in nearly a decade—either the worst or best way to get confirmed, depending on one’s view of the Senate.

Trump’s new nominee to be Secretary of Defense—known across government as “SecDef”—is Pete Hegseth. While he did serve as a military officer with tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, and founded a pro-veterans organization, the 44-year-old Hegseth is best known as a Fox News personality.

This background is atypical. Most SecDefs either have long experience running large organizations, participating in congressional committees with oversight of the military, were themselves leaders in the military or intelligence fields, or some combination of these qualifications. For example, Donald Rumsfeld, the only man to be SecDef twice, in the Ford and Bush administrations, was a Korean War veteran, former White House chief of staff, and the head of pharmaceutical and semiconductor corporations.

Richard Cheney, who would later become Vice President under George W. Bush, was SecDef under George H. W. Bush. Cheney was not a veteran, but had been White House chief of staff followed by a decade of congressional experience that included rising to Republican whip in the House. Notably, two long-past arrests for driving while intoxicated that would derail most military careers did not prevent him from running the military in what is largely seen as a successful tenure as it included the 1991 Gulf War—the last major conflict that America won unequivocally. Cheney’s subsequent bout of Trump Derangement Syndrome does not diminish this tenure as SecDef.

Credentials and experience do not guarantee success. Robert McNamara had both. He served in World War II and was later president of the huge Ford Motor Company. McNamara was SecDef under John Kennedy continuing into the administration of Lyndon Johnson as the United States escalated its military activity in South Vietnam into a full-blown war. He was the chief administrator of America’s first loss of a war and is perhaps the worst major U.S. government official of the 20th century (tracking nicely with Johnson, who competes closely with Jimmy Carter for worst president of the century).

Nevertheless, Congress will be surprised at the deviation from this norm with Hegseth’s nomination. So far, he probably tops the list of nominees on whom Democrats and the liberal media will train their fire. A potentially close vote also may mean that Republicans will have to slightly delay the confirmation of reported Secretary of State nominee Marco Rubio, as there will be a brief procedural gap between his retirement from the Senate and his replacement by a fellow Republican appointed by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis.

What might assuage concerns on Capitol Hill is not just sending Hegseth for the usual rounds of meetings with senators followed by a high-stakes hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee. It might also be necessary to sketch out who will fill out the rest of senior leadership at the Pentagon and what vision Trump has for the military given today’s threats.

After all, a SecDef must delegate most of his responsibilities. As head of the Defense Department and one of the original statutory members of the National Security Council, much of his time will be consumed with White House meetings, especially early in an administration. He will be one of just two civilians in the military chain of command (the other being the president). Some time-consuming administrative matters legally cannot be delegated: some SecDefs reserve Saturdays as “EXORD days” during which to sift through a massive number of execute orders moving forces around the world.

He must deal with commanders of the unified combatant commands, all of whom technically have a direct line to the president, as well as the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the head of which is the president’s chief military advisor. Then there are also the service secretaries (e.g., Secretary of Navy, Secretary of Army), who report to SecDef but have lots of power and friends on Capitol Hill. Some of these secretaries can help drive change (e.g., Reagan-era Secretary of Navy John Lehman), but they can also be obstructionist on behalf of their service (e.g., Bush-era Secretary of the Army Thomas White, whom Rumsfeld fired).

Unwritten requirements of the job are stealing turf from the State Department, which no matter how good the Secretary of State is, cannot be trusted to manage military relationships with allies and partners in key geographies like the Pacific and Middle East. (Luckily the SecDef basically has his own State Department in “OSD”—the Office of Secretary of Defense.) SecDef must also guard turf from the CIA and other intelligence bureaucracies, made a touch easier as much of the intelligence bureaucracy’s budget is laundered through the Defense Department.

Then there are the special requirements that will fall to the SecDef in this second Trump administration. The military Trump inherits is broken. It cannot win wars. It is at the same time bloated with a budget of nearly $900 billion while also somehow deeply under-resourced when it comes to procuring the weapons systems relevant to deterring war with China and Russia and putting terrorism-exporting Iran back in its cage. All of the services except for the Marines and Space Force are well below recruiting goals as young American eschew today’s woke military.

Trump used his presidential candidate’s prerogative of being vague about his plans for the military and national power more generally. That was fine for the election, but Congress can reasonably expect more detail now that Trump is set to be commander in chief. From his first term, the public and Congress know that Trump favors a strong military—in fact, MAGA foreign policy is often described as “peace through strength.” But the usual Republican method of fixing a depleted military is to throw lots of money at the Pentagon. This occurred when Reagan, George W. Bush, and Trump himself took over from Democrats. Unfortunately this is not an option with an annual federal budget of $7 trillion now including nearly $2 trillion in deficit spending despite the lack of a national emergency, adding ever more to the $29 trillion of national debt (excluding $7 trillion more in “inter-governmental debt”—IOUs from the Treasury to the Social Security Administration that are legerdemain).

Trump has not yet made clear whether he thinks some procurement reform and de-woking of the military, combined with his trademark diplomacy, will suffice—or whether he is willing to undertake the more radical reform that that military needs.

There are magnificent, highly capable weapons systems that simply need to be supplanted because the Ukraine War and other developments indicate current or future obsolescence. Doing so will alarm massive defense corporations as well as their lobbyists and congressmen, unless properly explained and undertaken in partnership with Congress.

For example, who doesn’t love aircraft carriers? I try to sit on the left side of a plane whenever flying into San Diego just to get a glimpse of any that happen to be in port. Unfortunately, new ones in the Ford class somehow cost $10-13 billion, not including their air wing. The new Columbia class of ballistic missile submarines is expected to cost $4 billion per boat, all to fire a nuclear system that is increasingly susceptible to missile defenses. The Army for some reason has a large presence in places like Italy and Germany, where fighting last occured in 1945. It also has vulnerable operations in Iraq, protecting a population that hates us. Its expensive presence in South Korea is decreasingly relevant to deterring either China or North Korea. The Air Force is proceeding with the B-21 stealth bomber at $700 million a pop, which is subsonic and has a human crew—pointless in an era of much cheaper and deadlier hypersonic missiles. Only the Marine Corps and the young Space Force have embraced change.

Essential activities, some of which overlap, might include:

Cancelling procurement of the systems identified above;

Rapidly launching a far greater number of Navy ships bristling with unmanned aerial vehicles and unmanned underwater vehicles;

Building, testing, and fielding a new generation of nuclear weapons mounted on hypersonic, maneuverable, and stealthy missiles and drones and spread across sea, air, and land forces—costly but far cheaper than conventional forces;

Removing troops and mothballing bases in Europe, which can pay to defend itself, and pivoting forces to the Indo-Pacific to deter China and Iran;

Incorporating the lessons from the Ukraine War of marrying high-tech intelligence collection and targeting with low-cost delivery systems like drones and century-old artillery technology;

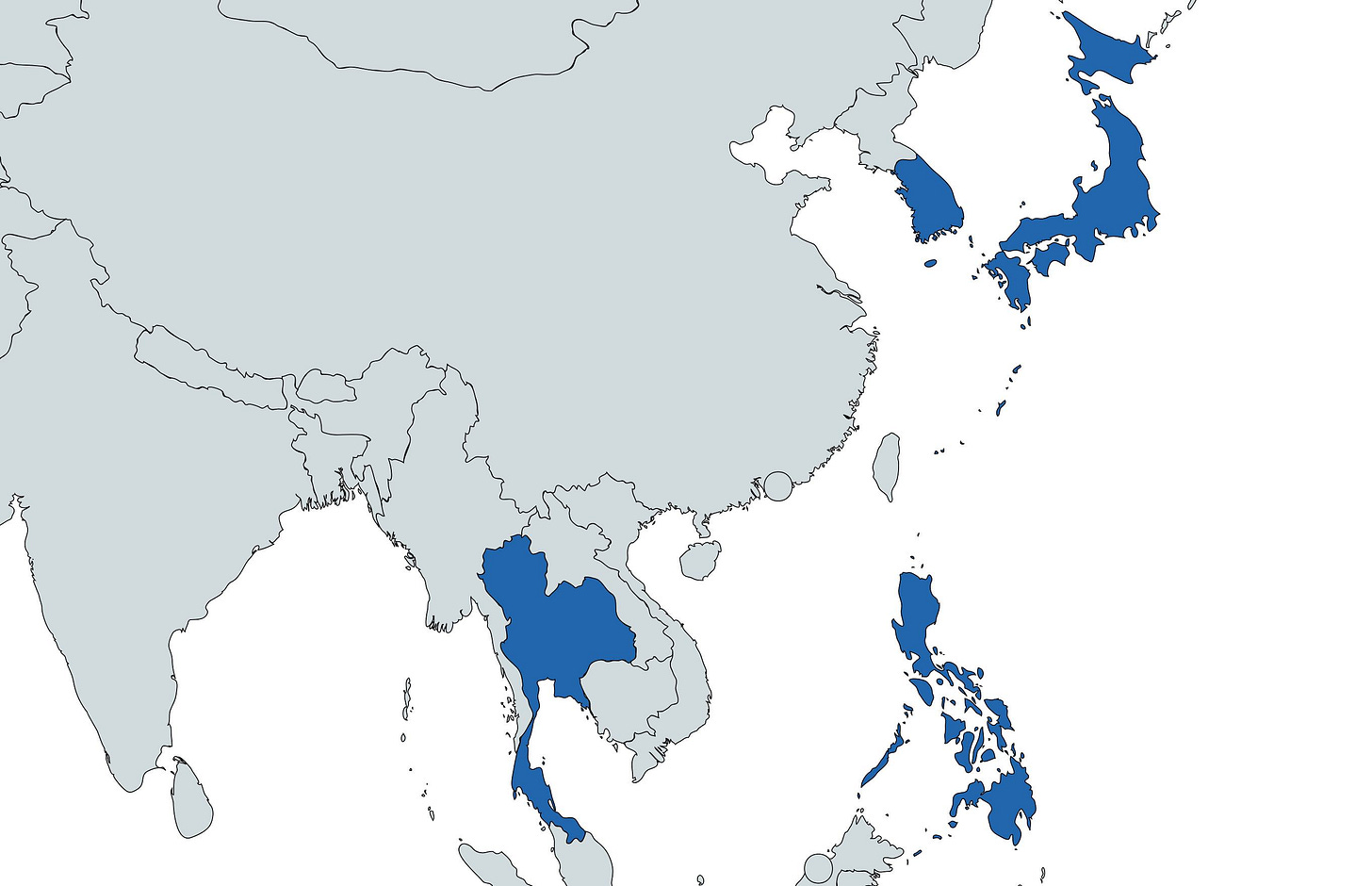

Building a clear defensive ring with our treaty allies in the Pacific running from Japan to the Philippines to Southeast Asia to contain China; and

Renaming the Defense Department as the War Department, as one of its predecessor agencies was called from the nation’s founding through World War II. There is a joke that the USA won every war before the creation of the Defense Department in 1947 and has lost every war since. While symbolic, changing the name would signify both an end to the woke war on masculinity and military qualities, but also an end to viewing the Pentagon’s job being one of ongoing gardening and churning. Instead, its job is to win wars. As the late Rush Limbaugh used to say, “The military’s job is to kill people and break things.” So be it.

These tasks would require enormous energy and effort in Washington and allied capitals. So would a much more basic plan of simply undoing the damage to military power caused by the Biden administration’s neglect of Middle East and Pacific allies, excessive focus on pointless Europe, and woke assault on military traits. Trump needs a team at the Pentagon that restores and transforms the military radically, while he and his economic team fix the economy and terminate sanctions and other abuses that threaten to undermine the U.S. dollar-dominated global financial system. These are the three pillars of restored national power.

Therefore it probably makes sense to identify who might accompany Hegseth to the Pentagon, especially his notional deputy secretary—who often “runs the building”—along with his under secretaries for policy and for acquisitions. Also important would be signaling who might serve as the service secretaries and senior officers who will support reform but who have credibility within the military services they would oversee.

An example: as World War II neared, General George Marshall was Chief of Staff of the Army—selected as a reformer by Franklin Roosevelt, who skipped over dozens of more senior generals to choose Marshall. The new Chief of Staff created what was called a plucking board to retire hundreds of senior officers who were too old or otherwise unfit for a wartime army. Imagine the cry if Roosevelt or Secretary of War Henry Stimson had done this himself?

By conveying to Congress that Trump envisions a team of reformers collaborating with it to change the military, along with necessary economic reforms and White House leadership, Trump can get his people in place. He could also start describing reforms by convening informal discussions that involve friendly members of Congress about what kind of budget request he will send them in spring for the fiscal year that starts next fall. This is the blueprint for running the government—and hopefully transforming the military.

All well and good but can he manage a bureaucracy with hundreds of thousands of employees? His resume sounds better suited to heading a Task Force or Working Group than day-to-day supervision of a nest of vipers--will his employees fear or respect him? Unless there's something someone hasn't told me, I doubt it. Management failure was Trump's downfall in first term, he lost control of the bureaucracy during the "Resistance" and never got it back. Are you really sure Hesgeth can cope with the required management tasks? I wish you could go into his managerial background some more...

Cost efficiency is one thing, but risking putting nukes on drone platforms sounds like the opening premise of a bad thriller you'd buy at the airport to kill time during a layover. Given our nation's track record with cybersecurity, ESPECIALLY as it relates to China, drones shouldn't be trusted with anything more dangerous than anti personnel weapons.